Perspectives

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought health inequalities to the fore, laying bare the issues and disparities that affect health outcomes. Poor health is by no means only due to individual behaviour, but also systematic differences which have created an unfair ‘postcode lottery’ of deprivation.

The 2021 COVID-19 impact report has exemplified the role health inequalities played in the high number of excess deaths in the UK. COVID-19 mortality rates in the most deprived areas of the UK were more than double those in the least deprived, and were almost four times higher for those under 65. This is due to a combination of working in front-facing care roles with fewer restrictions in locations that had to remain open, as well as a lower income with inadequate sick pay. In the face of the pandemic, these situational inequalities, combined with pre-existing differences in health, were associated with worse outcomes from COVID-19.

COVID-19 aside, we know that inequalities in health can impact on outcomes. For example, an individual born into a lower socio-economic status (SES) will probably experience lower levels of health, be more likely to smoke and suffer from obesity, and have a shorter life expectancy.

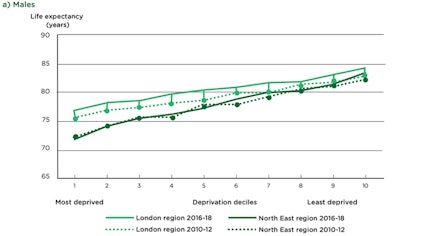

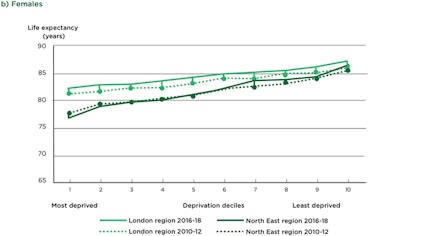

Figure 1: Life expectancy at birth by sex and deprivation deciles in London and the NE regions, 2010-12 and 2016-18

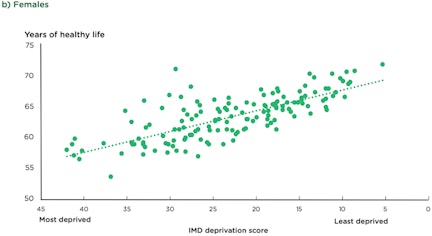

In the UK, the projected difference in life expectancy at birth between the most and least deprived areas was 9.5 years for males and 7.7 years for females in 2016–18. Life expectancy follows the social gradient in the UK which has only become steeper in recent years, with declining life expectancy for women in the most deprived 10% of neighbourhoods between 2010–12 and 2016–18 (figure 1). While the gradient of life expectancy is steep, that of healthy life expectancy is steeper, with those of lower SES expected to spend more of their shorter lives in poor health than those is less deprived areas (figure 2).

Figure 2. Healthy life expectancy at birth by Index of Multiple Deprivation score of upper tier local authorities, England, 2015-17.

You live a longer, healthier life if you are born in the right area

An example of this disparity can be seen in cancer diagnosis and treatment. When comparing cancer patients of a lower SES with those living in the least deprived areas of the UK: 20% are more likely to have their cancer diagnosed at a later stage; they receive only half the number of referrals to early-stage clinical trials; and face almost 25% more emergency admissions in their last year of life.

These stark facts highlight the physical and emotional needs of these individuals, which could arguably be improved if there were better prevention and detection measures in place, as can be seen in areas with better health outcomes. Cancer screening has shown to be a successful – indeed, vital – tool in detecting either pre- or early-stage cancer. Cervical screening is a great example: it is estimated that the ‘smear test’ has prevented 80% of deaths from cervical cancer since its implementation of the screening program in 1988. The earlier the cancer is diagnosed, the more treatable it is and the better the survival rates.

Screening saves lives, so why is it so challenging to get some people involved?

Uptake in screening programmes has been found to broadly mirror patterns of mortality. But if screening can help save lives, why don’t more people engage in it? It seems irrational not to participate in a behaviour that benefits our health. But behaviour is rarely as simple as that, and there can be many barriers to taking up screenings that may not be apparently obvious.

There are many factors – such as emotions (fear), past experience, social influence, the physical location of the screening centre, local transport routes, childcare/work commitments – that can influence whether or not someone participates in screening. Ultimately, knowing that screening is important is not enough, as information alone rarely encourages a change in behaviour.

As with all health behaviours, we must take a broad view and think about the context in which the behaviour does (or doesn’t) happen and consider the impact of the behaviour. And part of that context is the health inequality which the patient might face.

Understanding behaviour is the key to tangible change

Behavioural science can play a role by aiming to promote the following: good screening decisions, compliance with follow-up advice, communication of risk information, and understanding symptom reporting.

This was exemplified recently in a successful collaborative intervention between the Behavioural Insights Team and local government in Greater Manchester. The project adopted a simple nudge approach by sending previously eligible non-attendees of bowel cancer screening a reminder letter from their GP. The letter used anticipated-regret messaging, asking people to reflect on how they might feel should they be diagnosed too late. This simple intervention resulted in a statistically significant increase in the uptake of screening, demonstrating that easy, realistic, low-cost measures can be taken to improve health outcomes – simply by harnessing behavioural understanding and using this to nudge at the right time.

In the work of the behavioural science team at Hall & Partners Health, we aim to understand what a particular, potentially negative, behaviour is and how we can encourage a change to help people make better (and healthier!) decisions. Our team members have a varied and multidisciplinary background which gives us a holistic understanding of human behaviour – a perspective that is essential in health.

GET IN TOUCHWe recognise that while we alone can’t solve all health inequalities, we can use our knowledge and research to help encourage uptake of health-promoting behaviours. For example, we know the way something is presented to us can influence our perception of it, and that it also has a wider influence on our behaviour. Do I have the opportunity to get screened? Do other people like me get screened? How do I feel about getting screened in the first place?

The decision-making process is not linear. And the web of influences for choices regarding, say, cancer screening need to be understood so we can work towards healthier populations – particularly in a post-COVID era. Health inequalities are, in this way, critical to all health behaviours.

Think, think and think again.

Together we can mobilise change to tackle the growing number of health inequalities. What can you do?